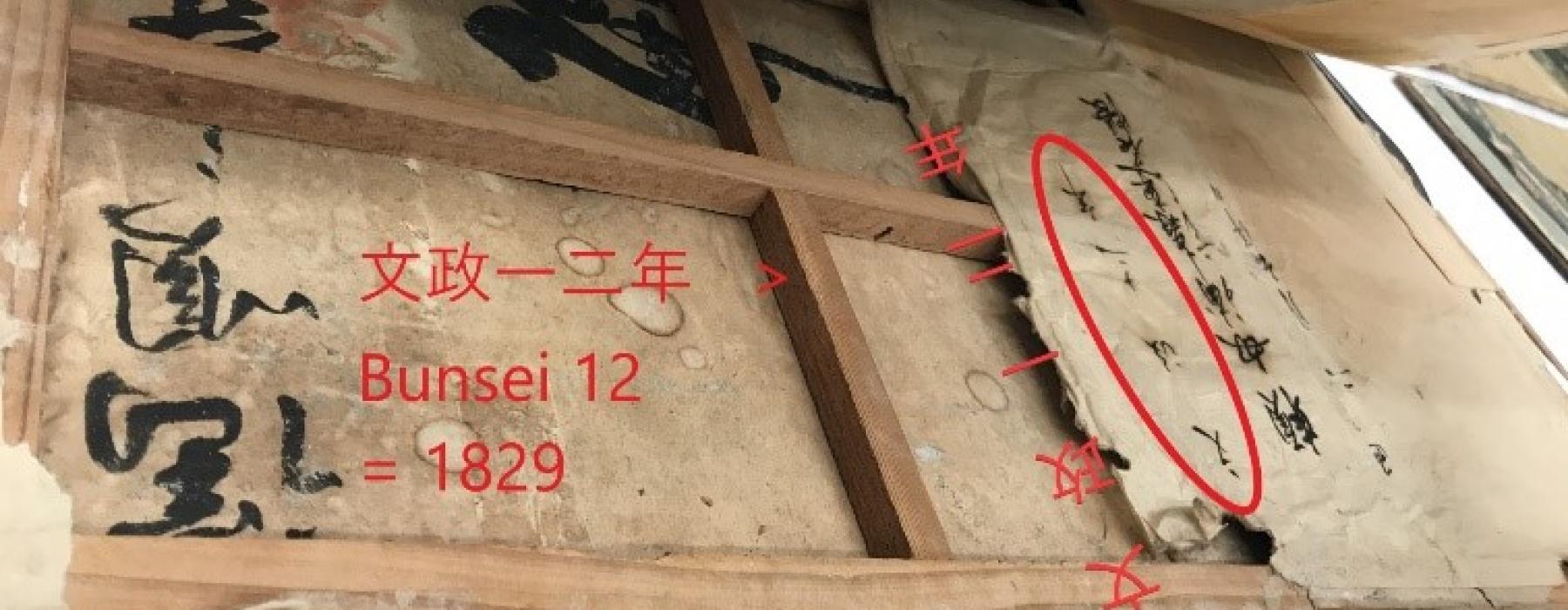

The restoration of the folding screen by Keiga has finally started and the first results of the research are in. Before work can start on restoring the painting itself, the folding screen has to be completely dismantled. This is an invasive job, but it also has a major advantage: old papers! Folding screens are generally lined on the inside with various layers of old paper; pages from account books, sheets used for calligraphy practice, personal memos, etcetera. These kind of papers constitute a very pure type of research material and they may hold information about the era in which the screen was created. Below are our first findings.

Time capsule from 1820s Nagasaki

The papers found inside the folding screen confirm that the screen was originally mounted in Nagasaki. We’ve already uncovered the name of a Chinese captain who sailed to Nagasaki, and the names of translators working for Chinese traders in the city. The Kunchi festival, for which Nagasaki is (was? Is it still famous?) famous, is also referred to indirectly. What’s more, all the dateable papers found so far pre-date 1836, the earliest possible year the screen could have been created.

That’s significant, because it indicates the Keiga screen has never been remounted. Traditionally, such folding screens are remounted at least once every century. Think of it as a kind of periodic maintenance that helps preserve the paintings. So why wasn’t the Keiga screen maintained? Probably because of the long time it’s been in the Netherlands. A century ago Japanese techniques for restoring folding screens were not available here. These days, we’re fortunate to have Conservation Studio Restorient in Leiden, who are uniquely specialised in Japanese folding screens and scroll paintings.

Recycled sliding doors?

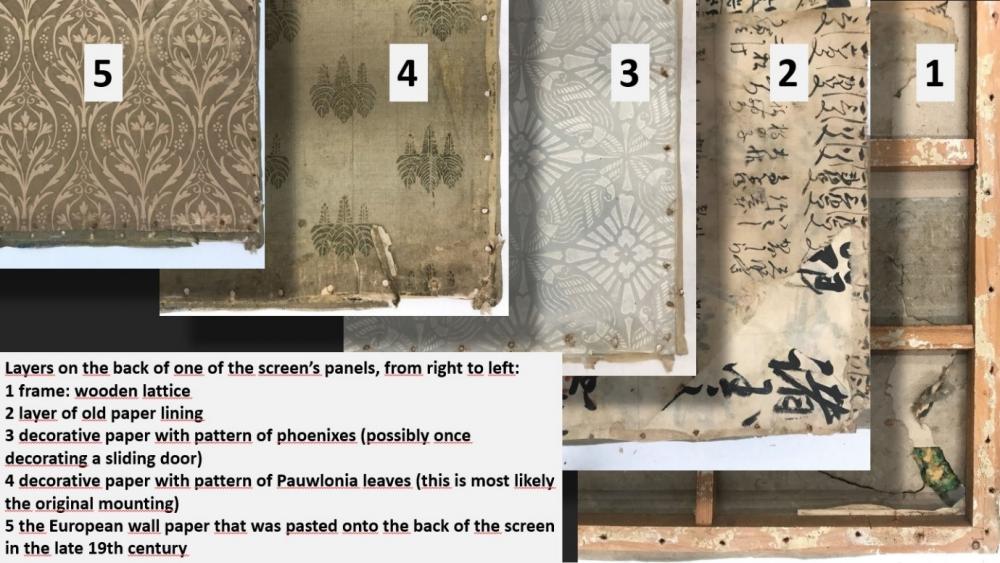

One of the more intriguing things we found was a circular hole in a layer of decorative paper. In itself it’s odd to use decorative paper on the inside of a screen. Such paper belongs on the back of a screen - on the outside, where one can see it – or on a wall or sliding door. The circular hole points to the latter: sliding doors often have circular handles, a type of sunken cup that corresponds to the size of the hole in the paper. Either the paper came from a sliding door, or entire sliding doors were recycled to create the panels for the screen. Of these two scenarios, the first is more likely. Taking decorative paper off a salvaged sliding door is easier than adapting an entire doorframe that’s not the same size as a folding screen. In any case, it appears that the makers decided to reuse parts from sliding doors to reduce cost. Creating an eight-panel folding screen, after all, can’t have been cheap. Just counting (skilled) labour, the large pieces of silk, the pigments and other materials, the costs must have been considerable. No wonder they tried to economise where possible, with cheap materials hidden away on the inside.

Expert meeting on the restoration

Shortly after dismantling the first panels, Museum Volkenkunde hosted a meeting with a number of experts in restoration, conservation, and Japanese art. With this international group of specialists, we discussed the dilemmas that are likely to come up over the course of the restoration. We addressed important questions such as filling in lost sections of silk, how to deal with pigment losses, and choices to make with regard to remounting the screen. Should we remount the screen with a decorative border on the front and a decorative paper on the back like the original first mounting? It is, after all, rather special to find these materials retained inside the screen. Usually these are lost due to past remountings. Or should we consider bringing back the European wallpaper that was pasted over the original decorative paper, since this has actually been on the back of the screen for most of its existence?

Because we’re still in the early stages of the restoration, we didn’t make any final decisions at our expert meeting. But the experts’ input was really valuable in helping us to assess the route to take in this momentous restoration. We have some time, though, because taking the screen apart – physically and in terms of research – is still very much ongoing. We’re looking forward to the new discoveries we’re expecting to come out of the screen’s lining papers…