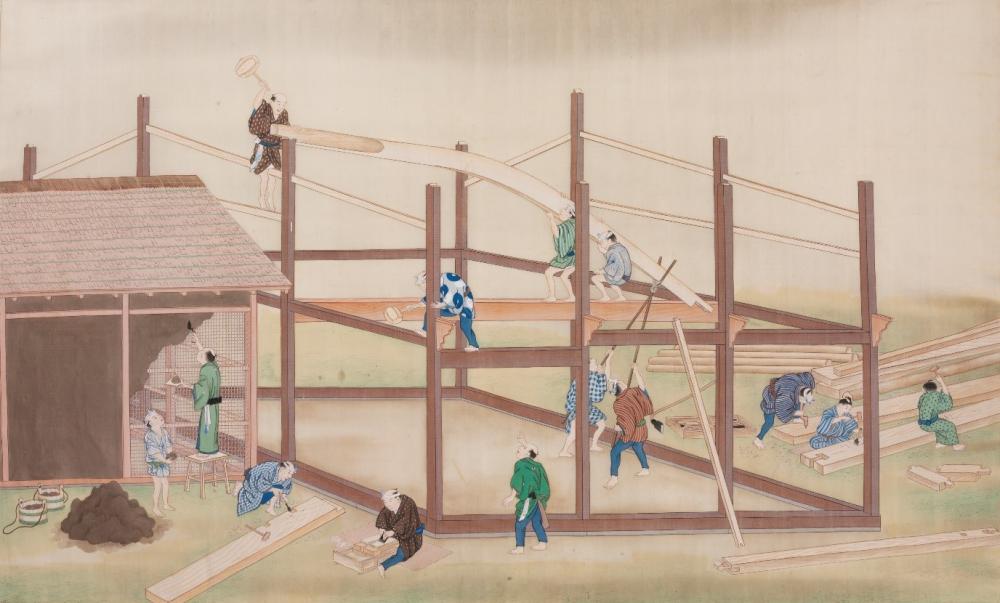

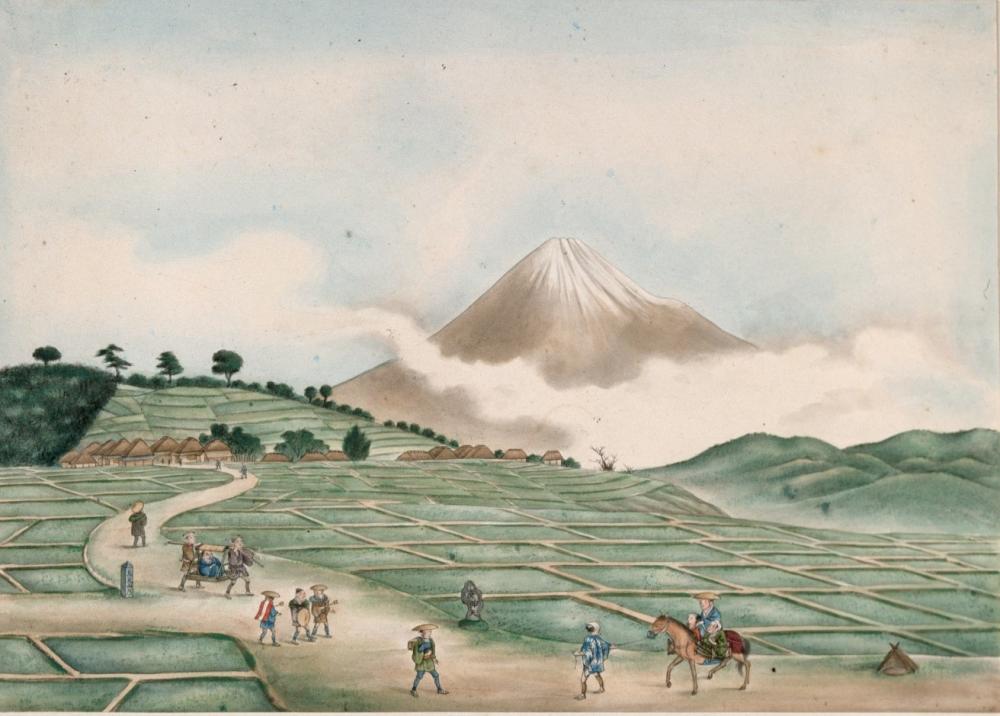

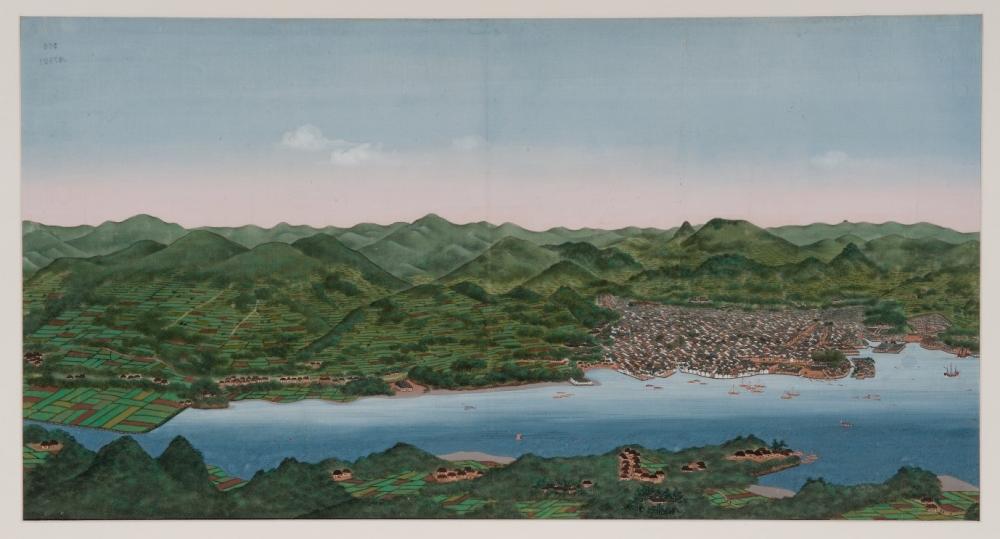

Over the course of his career, he created hundreds of paintings and drawings with the nature and culture of Japan as subject.[i] The National Museum of World Cultures keeps more than 500 works by Keiga and his studio in its collection. The great variety in Keiga’s oeuvre provides a unique insight into early nineteenth century Japan.