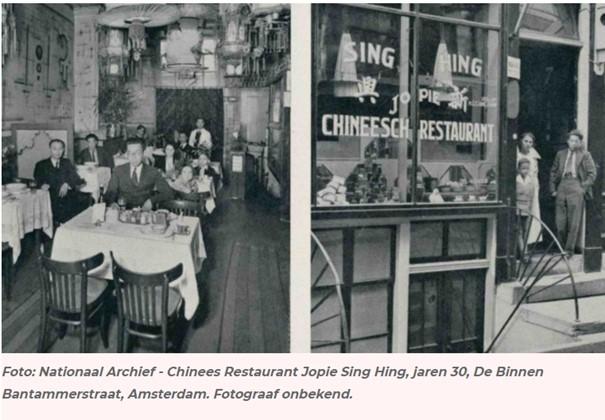

In the 1950s going to a Chinese restaurant was for many people in the Netherlands their first experience of ‘eating out’, not least because it was reasonably priced. These restaurants offered a mix of Chinese and Indies dishes.

Although the dishes were heavily adapted to suit Dutch taste, for many it was their first introduction to Chinese and Indies food.